PURITY, SHAME AND FALSE DIAGNOSES

What do psychiatry and psychology have to say about sexual and porn addictions?

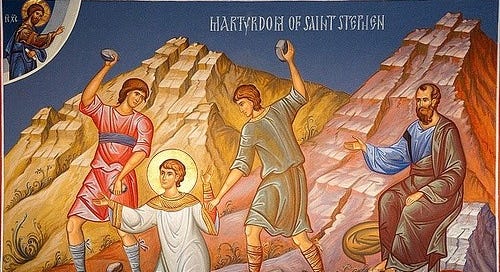

Martyrdom of Stephen, the first martyr

(This image is in the public domain under Creative Commons)

Introduction

Most Bible-reading Christians are well aware of Stephen, among the first deacons in the early Christian church and recognized as the first Christian martyr. In the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches, he is revered as both protomartyr and saint and venerated in iconic imagery.

What most also know about Stephen is that he was stoned to death following his “preaching” before the Sanhedrin. That speech is recognized as both a defense as well as one of the earliest and most powerful in the early church. And why was Stephen before the Sanhedrin defending himself? Because he has been accused of preaching blasphemy against Moses and God.

He was condemned by the Sanhedrin and was stoned to death for his bold preaching about Jesus Christ. His story is primarily found in Acts chapters 6 and 7 of the New Testament. What is often overlooked in this account is the foundational element that Stephen was falsely accused. False witnesses were brought forth to testify against him, and these deceptive testimonies led to his unjust trial and consequent stoning after he was declared guilty. Stephen is held up as not just a committed believer and a powerful speaker, but as a man unwavering in his faith. However, what cannot be avoided when considering this account is the fact that Stephen was falsely accused, and the consequence of that false accusation was life altering.

Very few people today are accused of preaching blasphemy, falsely or otherwise. However, an astonishing number of people are the victims of unjust treatment within the religious environment they grew up in or joined later in life. It’s not limited to the relatively small number of children now documented to have been sexually abused by clergy in the Roman Catholic as well as Protestant churches. False accusations with life altering consequences extend to the erecting of a religious moral framework that is contrary to human nature, to which compliance is rigidly expected. This is compounded in the case of human sexuality, by how often people get labeled as suffering from sexual addiction or pornography addiction.

Excessive sexual activity has been discussed, and written about for over a century, resulting in many opinions and some diagnostic classifications. Following decades of the growing lay use of the term, sexual addiction, there has been a steep rise in the corresponding lay “therapy” industry in the past few decades. This has taken place almost exclusively outside of mainstream psychology and psychiatry. A quick review of the bestselling authors of books about sexual addiction and its treatment find most of them to be graduates of bible schools or seminaries, not of universities with a psychology degree or medical school with a psychiatry degree. In the past decade, or so, psychological and psychiatric research has been conducted and published on both sexual and pornography addiction. What surfaces when this work is taken together is the fact that while there are specific diagnostic disorders in the realm of human sexuality, neither “sexual addiction” or “pornography addiction” are among them. Rather, what is emerging is more general agreement on the category of “compulsive sexual behavior disorder.” While the diagnostic criteria for it are still in the process of being defined, it is evident that sexual and pornography addiction are not accepted mental disorders in mainstream psychology and psychiatry.

In fact, sexual and pornography addictions are scientifically unsupported, and the therapies that have been developed to treat them are not supported by diagnostic criteria. In the world of psychiatry and psychiatry, it should be noted, lack of valid diagnostic criteria is a major obstacle to studying treatment outcomes.

What is Sexual Addiction?

What are sexual addiction and pornography addictions, and where did the concept come from? The diagnoses did not emerge out of the normal body of psychology and psychiatry dealing with addiction.

It’s important to begin with a clear understanding of what addiction is. According to the American Journal of Psychiatry it is a chronic brain disorder molded by strong biosocial factors. There are significant biochemical components of addictive behavior. “The risk for addiction is related to complex interactions between biological factors (genetics, epigenetics, developmental attributes, neurocircuitry) and environmental factors (social and cultural systems, stress, trauma, exposure to alternative reinforcers).”[i] In other words, addiction and addictive behavior are significant conditions, and the complexity means the label cannot be lightly applied.

The largely misunderstood fact is that mental disorders have specific diagnostic criteria resulting from scientific study and analysis. Sexual addiction and pornography addiction have never been accepted as tested and established mental disorders with corresponding diagnostic characteristics.

We need go no further than The Cleveland Clinic description:

Sexual addiction is an intense focus on sexual fantasies, urges or activities that can’t be controlled and cause distress or harm your health, relationships, career or other aspects of your life. Sexual addiction is the most commonly used lay term. You may hear healthcare professionals call this compulsive sexual behavior, problematic sexual behavior, hypersexuality, hypersexuality disorder, sexual compulsivity or sexual impulsivity.

Although sex addiction involves activities that can be common to a sex life — such as masturbation, pornography, phone sex, cybersex, multiple partners and more — it’s when your sexual thoughts and activities consume your life that you may be considered to have a sexual addiction.[ii]

Notice where the emphasis of that description lies: it is a lay term used to describe some intense behavioral practices, and while involving activities common to a sex life, the diagnosis only becomes appropriate when those activities consume one’s life!

Neither condition is found in the standard reference manual, the DSM-5 (the 2013 update to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders which is the taxonomic and diagnostic tool published by the American Psychiatric Association), nor in the ICD (International Classification of Diseases) listing published by the World Health Organization. What is accepted in the DSM-5 and the ICD-11 is the term, compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CBSD). This is important because it puts the focus where is should be – on “compulsive behavior” rather than subjective definitions of what is sexually normal.

Wikipedia provides a helpful overview:

Compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD), is a psychiatric disorder which manifests as a pattern of behavior involving intense preoccupation with sexual fantasies and behaviors that cause significant levels of mental distress, cannot be voluntarily curtailed, and risk or cause harm to oneself or others. This disorder can also cause impairment in social, occupational, personal, or other important functions. CSBD is not an addiction, and is typically used to describe behavior, rather than “sexual addiction."

CSBD is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an impulse-control disorder in the ICD-11. In contrast, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) DSM-5 does not recognize CSBD as a standalone diagnosis. CSBD was proposed as a diagnosis for inclusion in the DSM-5 in 2010, but was ultimately rejected.

Sexual behaviors such as chemsex and paraphilias are closely related with CSBD and frequently co-occur along with it. Mental distress entirely related to moral judgments and disapproval about sexual impulses, urges, or behaviors is not sufficient to diagnose CSBD. A study conducted in 42 countries found that almost 5% of people may be at high risk of CSBD, but only 14% of them have sought treatment. The study also highlighted the need for more inclusive research and culturally sensitive treatment options for CSBD. ICD-11 includes a diagnosis for compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD). CSBD is not an addiction.[iii]

Note the comment about mental distress related to moral judgment, because it is a critical part of distinguishing between the common, lay use of the term sexual addiction as an addiction disorder and the established DSM-5 and ICD-11 clinical definitions. As psychologist Craig Harper has pointed out:

...there are key aspects of the addiction definition that are not present in the description of compulsive sexual behavior disorder.[iv]

Of particular note in the ICD definition of compulsive sexual behavior disorder is the exclusion of a diagnosis if the cause of distress is linked to moral judgments of sexual behaviors, interests, or urges. This is important as it prevents diagnosis because of individual views about sexual behavior, with emerging evidence suggesting that this is precisely the driver of perceptions of 'sex addiction'.[v]

In lay terms, people with CSBD are viewed as suffering from hypersexuality. However, the studies by Harper and others prompt a very real question: if sexual and pornography addiction are not actual diagnostic categories, can hypersexuality even be considered a mental health disorder? There is still debate, however, but it’s worth noting that “The American Psychiatric Association rejected a proposal to include hypersexual disorder as a condition in DSM-5, their manual for assessing and diagnosing mental health conditions. Their reason was lack of evidence and the potential consequences of calling excessive sexual activity a “pathology” (calling it a disease or disorder).”[vi]

From a psychiatric and psychological perspective, then, the only valid diagnosis is compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CBSD). Even when the incidence is viewed through the broader lens of hypersexuality rather than just the more specific DSM-5 or ICD-11 definitions, the incidence is about only 3% to 10% of the general U.S. population. In other words, it is not the basis for labeling sexual addiction or pornography addiction a public health crisis as sixteen states have done![vii] Indeed, according to the same Cleveland Clinic article, the condition begins, on average, at 18 years of age, and 88% of those individuals have a history of other mental health conditions, such as:

Mood disorders, including bipolar disorder

Anxiety disorder

History of suicide attempts

Personality disorders

Other addictive disorders

Impulse control disorders

Obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD)

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

The moral framework and the range of what’s normal

The term moral framework in these studies by Harper and others essentially mean religious settings and the accompanying views of human sexuality derived from religions. Among Protestant denominations are the Puritans, from whom we get the term puritanical. The Cambridge dictionary defines puritanical as “believing or involving the belief that it is important to work hard and control yourself, and that pleasure is wrong or unnecessary.” Note the emphasis on pleasure, and especially sexual pleasure, as wrong or unnecessary. This strain of Protestantism traces back to John Calvin – one of the major early Protestant reformers in Geneva who was responsible for a theological system now referred to as Calvinism. He and his peers, propagated a doctrine of Total Depravity to describe the human condition. In this view, sex was to serve no purpose beyond procreation. Most of Protestantism accepts the concept that the result of the fall is total depravity, Roman Catholicism believes mankind to be fallen and sinful but possessors of free will and not totally depraved, and most Eastern Orthodox churches hold that human beings are fallen but were created good and are not intrinsically depraved.

Notwithstanding the theological distinctions, the fact is that all too many Christians subscribe to a puritanical and prudish view that sex and sexual pleasure are wrong, or at best, a necessary evil. Even for those that don’t subscribe to that extreme a view, sex and sexual pleasure are almost embarrassments, seldom discussed and characterized by furtive behavior. Consider the characterization of Victorian England with its rigid social norms, strict moral codes, prudish view of sex and sexuality, and an emphasis on propriety and restraint. Out of this negative view of human sexuality arises condemnation of much, if not most, sexual activity. For example, the short list of “common” sexual activity in the Cleveland Clinic definition (masturbation, pornography, phone sex, cybersex, multiple partners) are all considered to be wrong and/or sinful by most Christians. They are behaviors to be condemned and inclinations that must be overcome to remain in favor with God and within the community. Often shunning and rejection are used as tools to achieve compliance.

These are the theologies, doctrines, and views that build a moral framework out of which come proposed solutions. One such solution that began to appear in the late 1990s was the theory of sexual addiction, and it was soon followed by the subclassification of pornography addiction. It is no coincidence that this followed the appearance of the Purity Culture movement. The moral imperative was to overcome sexual urges and desires/ This stimulated the growth of an entire lay industry that positioned itself as “therapy” to help members, especially youth, overcome these urges and desires.

The result was that many of those who admitted to having these urges and desires were labeled as sexual or pornography addicts by these self-appointed experts in sexual purity. In addition, an entire culture grew up in religious circles wherein people uncritically accepted the premise and self-labeled as sex addicts.

...self-labeling as a 'sex addict' is driven in large part by an individual's level of religiosity and moral disapproval of sexual activity. Under this model, 'sex addiction' is not necessarily a description of excessive or problematic levels of sexual activity in terms of frequency, but is instead a label ascribed to sexual behavior that the individual finds morally wrong.[viii]

Another researcher in this area, Joshua Grubbs, goes so far as to observe that most often it is the religious beliefs that are the cause of the distress over these addiction labels. In other words, it’s the moral framework with a negative view of sex and pornography that can create mental health symptoms:

Religious beliefs about pornography, not the actual use, are often what predict mental health symptoms…We are not suggesting that people need to change their moral or religious beliefs, but it’s not helpful for someone with a low or normal amount of porn use to be convinced that they have an addiction because they feel bad about it.[ix]

Grubbs goes on to conclude, “mental health professionals must ensure their own biases don’t lead to inaccurate diagnoses.” In another study, Grubbs and his co-authors conclude:

Collectively, these findings suggest that perceived addiction to Internet pornography, but not pornography use itself, is related to psychological distress, which runs counter to the narrative that many people have put forth. It doesn't seem to be the pornography itself that is causing folks problems, it's how they feel about it…

Perceived addiction involves a negative interpretation of your own behavior, thinking about yourself like, 'I have no power over this' or 'I'm an addict, and I can't control this.' We know from many studies that thinking something has control over you leads to psychological distress.

Someone can be called out and publicly shamed, a marriage can become troubled, or maybe you are caught at work and get fired. Any of that causes psychological distress. We're only looking at one internal pathway -- what you perceive is bad but can't change due to addiction.[x]

Other researchers have come to similar conclusions:

Pornography addiction is a controversial concept, since it appears to be largely morally, ideologically, and politically motivated.[xi]

Which brings us to the necessary question of what’s “normal” and correspondingly, what is right? Among the best-known phrases to emerge from the US Supreme court was the 1964 statement by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart when he was asked to describe his test for obscenity. He responded: "I know it when I see it." While supporters praised it at the time, most now understand the statement to be wrong because it is based in arbitrary personal opinion. There is a difference between morals and ethics. Morality is personal, internal, and based in human practice of religious beliefs which define right and wrong. Ethics is external, communal, and dependent more on secular concepts like humanism. Asking the question, “what is normal,” as opposed to “what is right,” moves it out of the moral framework.

Members of religions uniformly claim that what is normal is what is morally right as embodied in their moral framework. While they are entitled to that view, it doesn’t work for science, or even in practice. As Ryan Anderson points out in a Psychology Today article, even what’s considered normal isn’t agreed upon. He describes a study of “unusual sexual behavior” which found that “many acts typically regarded as abnormal, or deviant are in fact reasonably common.”[xii]

He lists the following summary of the prevalence rates found for various sexual interests reported by the study participants:

Voyeurism: 34.5%

Fetishism: 26.3%

Exhibitionism, extended—had sex with a partner while someone else watched: 30.9%

Exhibitionism, strict: 5.0%

Frotteurism: 26.1%

Masochism: 19.2%

Sadism: 5.5%

Transvestism: 4.9%

As he points out, “a behavior is considered ‘statistically unusual’ if it occurs among less than 16% of the population, and ‘statistically rare’ if it occurs among less than about 2.3% of the population.” Most of these behaviors would be considered as paraphilic (non-normal), but it turns out that “paraphilia isn’t precisely defined,” and “exactly what is normal is still unknown.”

So where does Anderson end up? With this practical observation: “The bottom line is that nearly half of us admit to doing or thinking about doing something which isn’t considered sexually ‘normal.’ This is not something that is only done by non-believers. The Barna Group reported most recently that 54% of practicing Christians watch porn and 67% of pastors report “struggling with porn.”[xiii]

The consequences of shame and guilt

Christianity is multi-faceted, but a development that most can understand is the Purity Culture movement that swept into American Evangelical churches in the early 1990’s. The major theological motivations of Evangelical Christianity in the 1970s were not limited to the burgeoning anti-abortion movement. They sought also to maintain the traditional gender roles assigned to men and women by traditional Christianity, and from that sprang Purity Culture.

It was a movement that initially emphasized sexual abstinence before marriage but expanded in practice to the idea that to live a Christian life, boys and particularly girls, should suppress and repress all of their sexual thoughts and desires until they are married. It emphasized sexual abstinence before marriage and discouraged dating entirely to avoid the risk of premarital sex and maintain marital purity. Along with this came purity commitments and pressure to dress modestly to avoid arousing sexual urges. Masturbation was strongly discouraged, and non-heteronormative sex was strongly condemned. In many instances it involved church leaders pursuing details of youth’s sexuality and sexual relationships in one-on-one meetings. Group meetings became settings not just to instruct youth, but to convince and recruit them into deeper and deeper purity commitments.

A detailed example of one of these meetings forms the first part of the attached article by Dan Foster titled, “The Church Is Obsessed With Porn—But Not The Way You Think.”[xiv] It describes a meeting where youth are confronted by a person who claims to have recovered from porn addiction. The meeting then becomes a recruitment session ending with a call to action that involved making a purity commitment and signing a pledge card that stated: “I commit to a life of sexual purity — from this day forward.”

Foster’s article is subtitled, “What purity culture got wrong, what shame can’t heal, and why the real issue might not be lust.” It goes on to explain and demonstrate how what appeared to be the local church seeking to encourage its youth to pursue a life of purity was, instead, a structured methodology of control:

That night, they made it sound like porn was the front line of a cosmic battle. We were told that lust would ruin our lives. That every click was a step toward destruction. That purity was the ultimate test of our devotion. It felt urgent, spiritual, and eternal.

But looking back, I wonder if we were ever really fighting the right war.

Because the Church’s fixation on porn wasn’t rooted in a nuanced understanding of sexuality or a healthy theology of desire. It was driven by fear, moral panic, and a need to control what it didn’t understand. What we were offered wasn’t healing — it was surveillance.

Foster then describes a book by sociologist Samuel L. Perry titled, Addicted to Lust: Pornography in the Lives of Conservative Protestants, which documents that white evangelical Christians report the highest levels of guilt related to porn use — even though their actual consumption rates are comparable to, or even lower than, non-religious peers. Pornography shapes the lives of conservative Protestants in ways that are uniquely damaging to their mental health, spiritual lives, and intimate relationships.[xv]

Foster’s telling observation is: “In other words, evangelicals aren’t necessarily watching more porn. They’re just drowning in more shame about it. This isn’t a war on porn. It’s a war on self.” And there are real consequences:

While we were busy confessing impure thoughts to youth leaders and breaking down in small groups, we weren’t taught how to understand our own humanity. We weren’t offered a positive vision for sexuality — only rules, restrictions, and rituals of guilt.

We learned how to manage sin. We never learned how to make peace with ourselves. And maybe that’s the false war: not just that we were fighting porn, but that we were taught to fight ourselves — our instincts, our bodies, our longing for connection.

Which brings us to the difference between guilt and shame. Alexander Lang, of Restorative Faith, has among the simplest and most accurate descriptions when he’s talking about the consequence of the purity movement:

…these adolescents are taught to feel not just guilt, but deep shame around anything sexual. It’s important to distinguish between shame and guilt. Guilt is when our conscience tells us that we've done something wrong. Shame, on the other hand, makes us feel condemned to our very core. It causes us to question our worth and our integrity and sexual shame is particularly damaging in this way because Evangelical culture approaches sexuality like a light switch that you can choose to flip on at any moment.[xvi]

All of which brings us back to the initial subject of sexual and pornography addiction and the therapies that grew up around them. Common sense says it’s bad practice to develop therapies for questionable conditions, particularly ones that don’t have scientific diagnostic criteria and are not accepted by psychiatry or psychology. In that regard, they are much like conversion therapy to cure homosexuals – another non-scientific therapy that has been thoroughly debunked. In fact, these therapies are a cottage industry that grew up in religious circles to “treat” those found to have the conditions that were part and parcel of the purity movement. These so-called addictions are not supported by research or study, and the offered therapies are not mainstream within psychiatry or psychology either. They are inherently dangerous and potentially very damaging.

As Amee Baird summarizes:

Although it is a "nice theory", empirical support for it is largely missing…[ the] industry of porn/sex addiction is based on conservative moral values around sexuality that intrude into clinical practice.[xvii]

Life-altering consequences

Dan Foster’s piece about the church and pornography concludes by returning to the youth meeting where attendees were recruited to sign a purity promise card, which unwittingly committed them to a life of denying, repressing, and ignoring normal sexual urges and desires as well as carrying the accompanying internalized shame.

Looking back, I don’t think what we needed was more urgency or more rules. We needed someone to help us understand why we were struggling in the first place.

Not just how to stop, but where it came from, what it meant, and how to live in a body without being afraid of it. The Church could have offered that. It still could.

Imagine if instead of teaching us to fear our bodies, the Church had taught us to inhabit them. Imagine if confession wasn’t about punishment, but about integration. Imagine if desire wasn’t demonized — but dignified, examined, and gently guided.

Psychology tells us this is not only possible — it’s essential. Spirituality tells us it’s not only essential — it’s sacred.[xviii]

Healing. That’s what the church should be about. The operational model of the early church, especially in the East, was that the church was a hospital. Hospitals accept the infirm and injured for treatment to make them whole and well. Among the worst things that can happen in a hospital is a wrong diagnosis because it can result in treatments that not only don’t help but can do even more damage.

What about false diagnosis?

That’s the question we are left with. If sexual addiction and pornography addiction are not accepted mental conditions with tested and accepted diagnostic definitions, then to diagnose someone as suffering from either is to apply a false diagnosis. A diagnosis is a label, and to falsely label someone is not just to apply a term that is incorrect, but it means the person almost always internalizes this distorted way of thinking about themselves. Those distortions become patterns of thinking that are internalized, and the person often doesn’t realize they have the ability to change them—they accept that the label came from an authority figure and that’s the way things are.

As previously described, a cottage industry of therapies for these so-called addictions has grown up based on conservative moral values that intrude on clinical practice. Most of those therapies are outside of mainstream psychiatry and psychology and based on religious moral principles that often are at odds with clinical practice. What happens when the application of a false diagnosis is compounded by therapy that is outside mainstream psychiatry and psychology?

We’re left with the possibility that somehow, and someway, the application of both false diagnosis and false therapy may benefit some people. However, in the case of the majority, what has been done is apply false labels to people – labels that they carry with them for the rest of their lives. There are not only immediate consequences like being shunned, expelled from school, or fired from a job, but there are deep, personal consequences imposed when people are labeled with a false condition that is built around shame, guilt, and a denial of normal sexual impulses and desires.

Lang discusses the work of Linda Kay Klein, who observes that a result of the purity movement in evangelicalism is a “sex shame brain trap” – meaning many find they cannot have a normal sexual relationship. Because of a lifetime of repressed sexual desires, the moment these people engage in sex, it triggers a shame reaction, and often sexual dysfunction. Lang observes:

I personally encountered this type of theology among the Christian groups I attended at Rice University in Texas and within Evangelical churches in California. I experienced first-hand the great shame and judgment levied against anyone who would question the Evangelical attitude towards sexuality. When my wife and I skirted some of those norms when we were first dating, she was quickly blacklisted by her community.

I also think this hyperfocus on sexuality is why these communities will also obsessively rail against homosexuality as a sinful aberration. Same sex relationships threaten the entire foundation of their theology.[xix]

This shame-based approach to sexuality is bad enough without adding to it all the pain and baggage that comes with the false diagnosis of sexual or pornography addiction. To label a person a sex addict or a porn addict is to other them—to place them in a different category of being. They are no longer like us; they are that thing. They are no longer homo sapiens but rather homo depravus. As one person, so labeled, observed after beginning the process of overcoming the label and getting out from under the life-altering baggage: “Half a lifetime of crushing shame and guilt were the result, however, and I am working my way through that with a little help from my friends!”

Final thoughts in closing

False diagnosis causes significant levels of mental distress, cannot be easily overcome, and frequently leads to contemplating self-harm. In other words, the false diagnosis causes the very thing it’s supposed to cure and can also cause impairment in social, occupational, personal, or other important functions.

As we’ve seen, the perceived addiction causes the harm; the shame hurts more than the behavior. The life-altering impacts of a false diagnosis and the label it attaches, followed by a therapy built to treat the false diagnosis, is often life altering and very difficult to recover from.

If you’re reading this and have any involvement in applying these false diagnoses of sexual addiction and/or pornography addiction, you need to stop! If what you’re doing is principally driven by your beliefs and moral framework, you need to seriously assess why you’re doing so, since it’s at odds with the science. Far more people are hurt or permanently damaged by these labels and the consequent therapy than benefit. Trying to change, deny, overcome, or erase natural sexual desires and urges is a nonstarter. It will not only not work but does real damage.

If you’ve received one of these false diagnoses and were sent to therapy for it, the odds are that you are still struggling because no therapy can make a natural urge or desire go away. At best they can provide a way to repress them. They’re still there, and so is the shame and guilt, and you need to understand what has been done to you. Many counseling centers nationwide are now developing focus areas in recovering from purity culture, and Sojourners published a page of resources to help people become more and informed and begin to recover.[xx]

You’re not depraved or monstrous, and you’re not alone. You need to get real help for the real damage likely caused by the labeling of the false diagnosis and the damage caused by the scientifically unsupported therapies. You need to do this to find true freedom from the shame and false guilt that was laid on you by the purity movement simply for being a sexual being.

References

[i] Neuroscience of Addiction: Relevance to Prevention and Treatment; American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 175 No. 8, 2018

[ii] Cleveland Clinic: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22690-sex-addiction-hypersexuality-and-compulsive-sexual-behavior

[iii] Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compulsive_sexual_behaviour_disorder

[iv] Craig Harper; Why Sexual Addiction May Be A Myth; Psychology Today, 12/24/21

[v] Harper, ibid

[vi] Cleveland Clinic; ibid

[vii] Governing: https://www.governing.com/archive/gov-pornography-public-health-crisis-states.html

[viii] Harper, ibid

[ix] Grubbs, Joshua; American Psychological Association press release on the publication of “Moral Incongruence and Compulsive Sexual Behavior: Results From Cross-Sectional Interactions and Parallel Growth Curve Analyses” by Grubbs, et al; 2020

[x] Joshua Grubbs, Nicholas Stauner, Julie Exline, Kenneth Pargament, Matthew Lindberg; Perceived addiction to Internet pornography and psychological distress: Examining relationships concurrently and over time; PubMed, 2015

[xi] Williams, DJ; Thomas, JN; Prior, Emily,; Are Sex and Pornography Addiction Valid Disorders?, 2022

[xii] Ryan Anderson; How Do You Define What Is Sexually Normal?; Psychology Today, March 2016

[xiii] Barna Group: https://www.barna.com/research/pastors-pornography-use/

[xiv] Foster, Dan; The Church Is Obsessed With Porn—But Not In The Way You Think; published in Backyard Church on Medium, May 21, 2025

[xv] Samuel L. Perry, in Addicted to Lust: Pornography in the Lives of Conservative Protestants, (Oxford University Press USA, 2019)

[xvi] Lang, Alexander; A History of Purity Culture, published on Restorative Faith: https://www.restorativefaith.org/post/a-history-of-purity-culture

[xvii] Baird, Amee; Porn On The Train (And On The Brain), 2020; Columbia University Press

[xviii] Foster, Dan; ibid

[xix] Lang, Alexander; ibid

[xx] Sojourners; July 19, 2023: https://sojo.net/articles/healing-leaving-recover-purity-culture-Christian

Thank you for this. Very well presented. As someone who was not only raised in purity culture as a male, but has been married to a purity-culture-mongering woman for over 20 years, I keenly know the feeling that the misdiagnosis of shaming every man who has ever looked at porn more than once as a sex addict has been disastrous. And adding the spiritual elements of “you must be misunderstanding the Gospel, otherwise you would find freedom” or “You ARE an Adulterer. Jesus said so.”

Add to that the simultaneous defense of king David and his concubines as being a “man of his times” while quoting his psalms to you for healing from dipping your toes into what is normal for men of our times.

Christians are a mess. It’s a good thing we don’t get our identity from our fellow Christians. That comes from our Father. Unfortunately, what we do get from our brothers and sisters is a good deal of shame.